Can one Note Change your Heartbeat?

What a “Future Friday” Study Taught us about Pure Tones, Stress, and Performance

Sound is a sense we rarely escape. While closing your eyes eliminates sight and pinching your nose mutes smell, blocking hearing is a far greater challenge. Even with your hands pressed firmly against your ears, a faint muffled thrum remains. Proof that sound is one of the most persistent connections to our environment. This persistence may be one reason architectural design has historically prioritized the visual: sight demands more of our brain’s active resources, so spaces are often shaped to please the eye. Yet we rarely encounter sound as a single, isolated event. During each day, we move through various soundscapes—the layered, shifting weave of tones, rhythms, and reverberations that surrounds us and gives a place its audible identity. In concert halls, clubs, and theaters, acoustics are carefully tuned, making sound integral to the experience, but in everyday settings sound also quietly steers our attention, shaping mood and emotion through its smallest nuances. This raises an intriguing question: could the everyday be engineered to enhance well-being—amplifying calming frequency while dampening those that disrupt?

The psychological effects of music have long been recognized, with commercial spaces carefully curating playlists to influence mood and behavior. Yet scientific investigations often concentrate on complex compositions or broad categories like ambient noise, which makes it difficult to pinpoint which specific elements—melody, rhythm, or frequency—are actually driving changes in emotion or cognition. Studies that reduce sound to a single pure tone are uncommon, even though this kind of minimal stimulus is precisely what allows clean attribution. The long-running debate around concert pitch (standard 440 Hz) versus the so-called “natural” pitch (432 Hz,) offered a clear and practical framework for our pilot study. By stripping away rhythm, melody, and lyrics and focusing solely on frequency, we aimed to examine how minimal soundscapes interact with both physiological and cognitive responses.

Figure 2: Methodology – Each participant completed basic arithmetic tests on a laptop. During rest periods participants were either silent or exposed to a particular sound frequencies. Each participant wore a smart watch to measure their physiological state (HR).

In our experiment, eleven participants drawn from backgrounds in engineering, architecture, and design entered an acoustically treated room to complete a series of arithmetic tasks. The problems, randomly generated and involving numbers zero to twelve with basic operators, were presented on a laptop in blocks of 30 seconds separated by rest periods of 45 seconds. During these intervals, participants either sat in silence or were exposed to a continuous tone at either 440 Hz or 432 Hz. Throughout the session, heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) were measured continuously using an optical sensor worn on the wrist, while the software recorded reaction times and accuracy for every trial. In total, the study captured more than 3000 cognitive trials and approximately 90000 heartbeats. Notably, a technical fault prevented one participant from experiencing the 432 Hz condition, and this individual’s data was excluded from analyses involving that frequency.

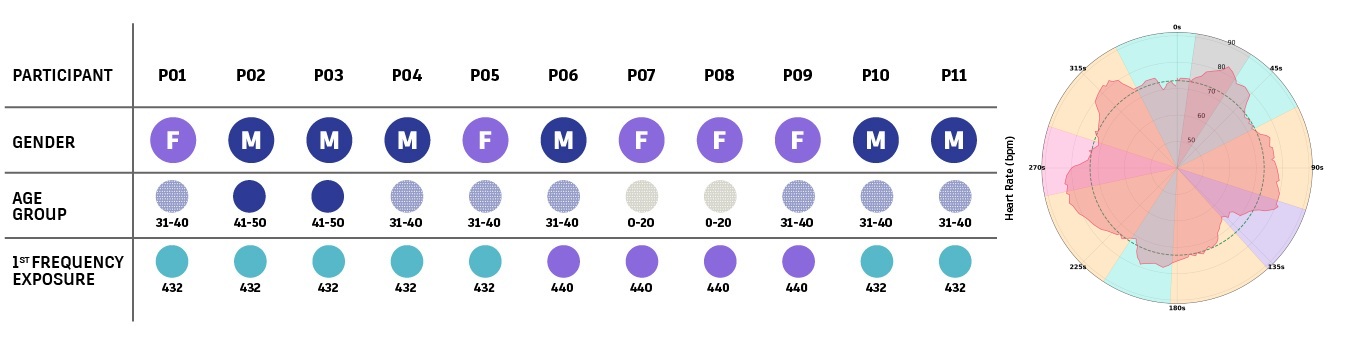

Figure 3: Demographic of the sample population. Of the 11 participants, gender, age and first frequency exposure are presented. The circular figure is a representation of the HR during the test. Colors represent phase (yellow = practice, green = rest, orange = test). Total duration of the test was 360s = a full circle. Dotted line is resting HR baseline – confirm standard.

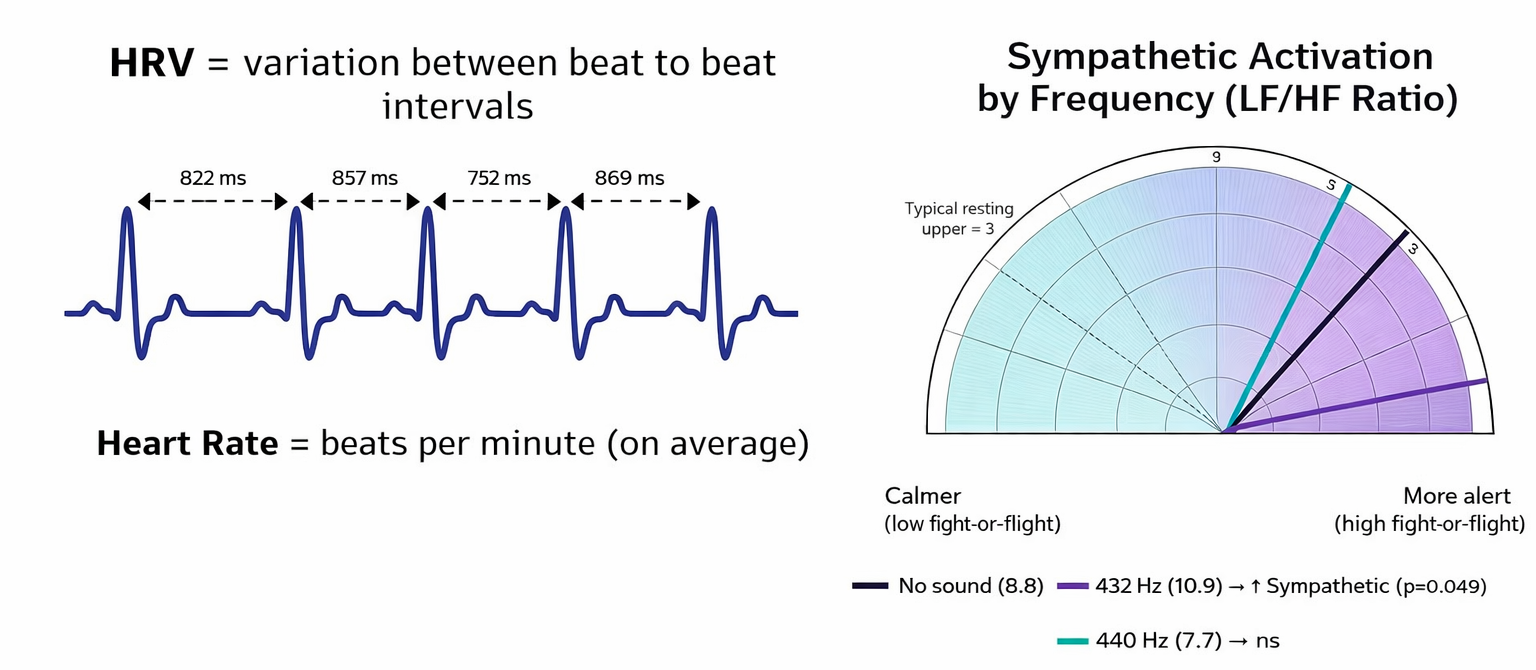

Despite the modest sample size, the results revealed a discernible pattern. Exposure to the 432 Hz tone during rest was associated with a significant increase in the Low Frequency to High Frequency (LF/HF) ratio, a metric of sympathetic nervous system activity, compared to baseline. This finding suggests that participants remained stimulated rather than progressing towards relaxation in line with the baseline tests. This result challenges some common assumptions about lower pitch frequencies. Interestingly, arithmetic reaction times following 432 Hz exposure were on average twenty milliseconds faster than after other conditions, hinting at a subtle cognitive effect. However, it is essential to interpret these findings with caution. The LF/HF ratios observed were consistently above the range considered healthy for resting individuals, likely reflecting the demanding nature of the cognitive task and the artificiality of the experimental setting. The small, non-representative sample, combined with the controlled and unusually quiet environment, limits the generalizability of these outcomes. Additionally, the order of sound exposures was not counter-balanced, leaving open the possibility that sequence effects influenced the results. Occasional missed answers and implausible responses further highlight the challenges of real-world data collection.

Figure 4: HRV visual explanation. HRV is more useful than absolute HR readings to infer physiological state/shifts. Its the measure of variation in time between heartbeats vs simple beats per minute. (Right) speedometer style gauge showing the effect of sound exposure on HRV relative to no sound exposure. 432 (purple line) illustrates a statistically significant shift into the sympathetic state (stressed) vs the baseline (black) and a less statistically significant reduction from 440hz (teal).

Although, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from a pilot of this scale, the study’s design and results point toward important avenues for future research. If something as simple as a frequency shift of merely 8 Hz can alter physiological state and cognitive speed, even modestly, then the acoustic dimension of space deserves far greater attention in design practice. It invites us to consider not only how to add beneficial sounds, but also how to identify and mitigate those that may be detrimental to health and performance. As technologies for environmental sensing and artificial intelligence advance, our ability to understand and optimize the multisensory experience of built spaces will only increase.

Figure 5: With more people living in the built environment, coupled with the increase in human activity. and technology present in our spaces, problematic noise frequencies are increasing. Understanding the interplay between these noises and our own physiological wellbeing is becoming a real consideration for urban design.

This raises an intriguing question: could the everyday be engineered to enhance well-being by amplifying calming frequencies while dampening those that disrupt? The answer depends not only on architecture, but on everything we choose to design and make. Materials, surfaces, products, systems, and technologies all contribute to the soundscapes we inhabit, whether intentionally or by accident. If sound is inseparable from place, then design is already composing daily life by deciding what resonates, what reflects, what masks, and what intrudes. Broadening design beyond pure function invites a richer mandate to enliven experience as well as enable it, shaping environments that do not just work, but feel better to live in, audibly, emotionally, and socially.

Think you can feel the difference? For those curious about their own response to sound, the arithmetic game used in the study is available to try. You can test yourself with the 45-second arithmetic game or try the one we used in the study and see whether a tiny pitch shift changes your own scores.

Get in touch

Have we piqued your interest? Get in touch if you’d like to learn more about Autodesk Research, our projects, people, and potential collaboration opportunities

Contact us